Historical Roots, Early Concepts, and Research Legacy

by Dr. Andreas Neus und Professor Björn Ivens, Otto-Friedrich-Universität Bamberg

Professor Ludwig Erhard, Professor Wilhelm Vershofen, and GfK-CEO Dr Georg Bergler

About Utility Concepts and Market Decisions

The Nuremberg Institute for Market Decisions (NIM) has been operating under this name since 2018. However, its historical roots go back much further. NIM was founded in 1934 under the name Gesellschaft für Konsumforschung e.V., or GfK for short. The founding fathers Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Vershofen, Dr. Erich Schäfer and Prof. Dr. Ludwig Erhard pursued the goal of “making the voice of the consumer heard”, as the scientist and author Vershofen put it in a nutshell. Pioneering concepts by Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Vershofen – such as the analysis of the conceived benefit, his transaction model underlying the purchase decision (and the sales decision) or understanding the visible market decision based on initially invisible attitudes and habits of the consumer are still highly topical today.

As early as the 1920s, Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Vershofen was convinced that business administration and economics paid too little attention to the actual core of market activity. Indeed, he identified a blind spot where all market decisions are made and where the success or failure of products is decided: with the consumer. On this basis, he began lecturing and researching at the Nuremberg School of Management on “The Study of the Human in the Marketplace.”

In doing so, he strongly criticized consumer research by traveling interviewers using quantitative scales, which was common in the U.S. at the time. Vershofen criticized the fact that this method produced rather superficial figures since the interviewers, who were only “passing through” an area, did not understand the daily reality of the respondents’ lives and were therefore unable to fully interpret figures that their scales yielded. He was certain that the actual background and motives – the “why” of a market decision at the individual level – could not be adequately captured by the methodological approach dominant in the U.S. at the time

To solve the problem of the lack of an empirical basis for a deeper understanding of the consumer, Vershofen founded the Gesellschaft für Konsumforschung e. V. in 1934 as a close partner of his institute for the economic observation of German finished goods (Institut für Wirtschaftsbeobachtung der deutsche Fertigware). His approach was to build up a network of correspondents to overcome the empirical deficits he had identified in understanding consumers’ market decisions:

Professor Wilhelm Vershofen

- The correspondents themselves lived in the “districts” where they conducted interviews and therefore knew the reality of life on the ground.

- They usually conducted interviews at the respondents’ homes, providing even more context.

- The interviews were semi-structured and thus also open to ”soundbites”, which could provide important qualitative information on the motives and habits underlying purchasing decisions. It also allowed the correspondents to feed back specific problems and suggestions for improvement to retailers and the industry, which they did.

In 1934, Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Vershofen had already begun to unearth a rich treasure trove of information on market decisions. At the time, a large-scale study cost 20,000 Reichsmarks – comparable to around €100,000 today. Such Studies were used to gather up to 10,000 consumer voices. The basic idea was always that, after an embargo period of five years, the data from the specific studies conducted on behalf of individual companies should also be available to the scientific community to allow thorough analysis and the generation of more general insights on market decisions.

Together with his colleagues, Vershofen pursued the goal of “making the voice of the consumer heard” like no else at the time – and he achieved it. At the time, his research approach and the resulting understanding of consumers’ motives and habits were unique in the world. Today, we would speak of qual at scale – a discipline that was only “rediscovered,” as it were, by leveraging the internet and advances in the field of computational linguistics

In the present day, it is becoming increasingly clear that the economically decisive factor is the consumer in the sense of the end user. The fate of all products, which have been manufactured for the market – that is, for sale – ultimately depends on his attitude, his habits and his market decisions.

Professor Wilhelm Vershofen, Memorandum, 1934

Highly Relevant Concepts and Research Topics - Also for Today

A whole series of visionary and still-relevant concepts emerged from the research of Vershofen’s team, such as a detailed nomenclature for understanding utility from the consumer’s point of view, a transaction model and various methodological innovations. Today, we would group together many of his themes and theses – the critique of homo economicus and the seemingly “irrational” behavior of consumers – under the term “behavioral economics.”

In addition, Vershofen and his team dealt early on with substantive issues such as the impact of new technologies on markets and the problems they created. Cost-efficient mass production, for example, also led to negative consequences in the market because products could be produced more cheaply in large numbers than before, though at the cost of a reduced variety of variants. This led to a poorer fit between supply and individual demand. This problem – having to accept paying for features you did not need, or the lack of features you did need – was what Vershofen called “exchange residuals.”

Vershofen criticized the fact that the economic advantages of standardized mass production created a temptation to overcome the sometimes poor fit through increased marketing efforts, rather than actually solving the underlying problem by developing more precisely tailored offerings to match consumer needs. He thus explicitly went into opposition to Henry Ford, who demanded that his salesmen convinced their customers that the offer met their needs – even if the customers disagreed. Ford’s approach resulted in the famous statement: “Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants as long as it is black.”

Vershofen, on the other hand, saw raising the quality of our understanding of what benefits customers really valued as a central factor for a well-functioning and efficient market. The effort to fully understand and explore the implications of microeconomic decisions of producers, retailers and consumers and their aggregated macroeconomic impact on the market and society as a whole runs through Vershofen’s writings. This macroeconomic perspective was later developed further by Prof. Dr. Ludwig Erhard.

Both Vershofen and Erhard also looked closely at the tension between increasing consumption and sustainability in the face of limited natural resources from the 1940s onwards. Both were convinced that in a society, each individual consumer must decide how to value money and material goods on the one hand and time, nature and quality of life on the other.

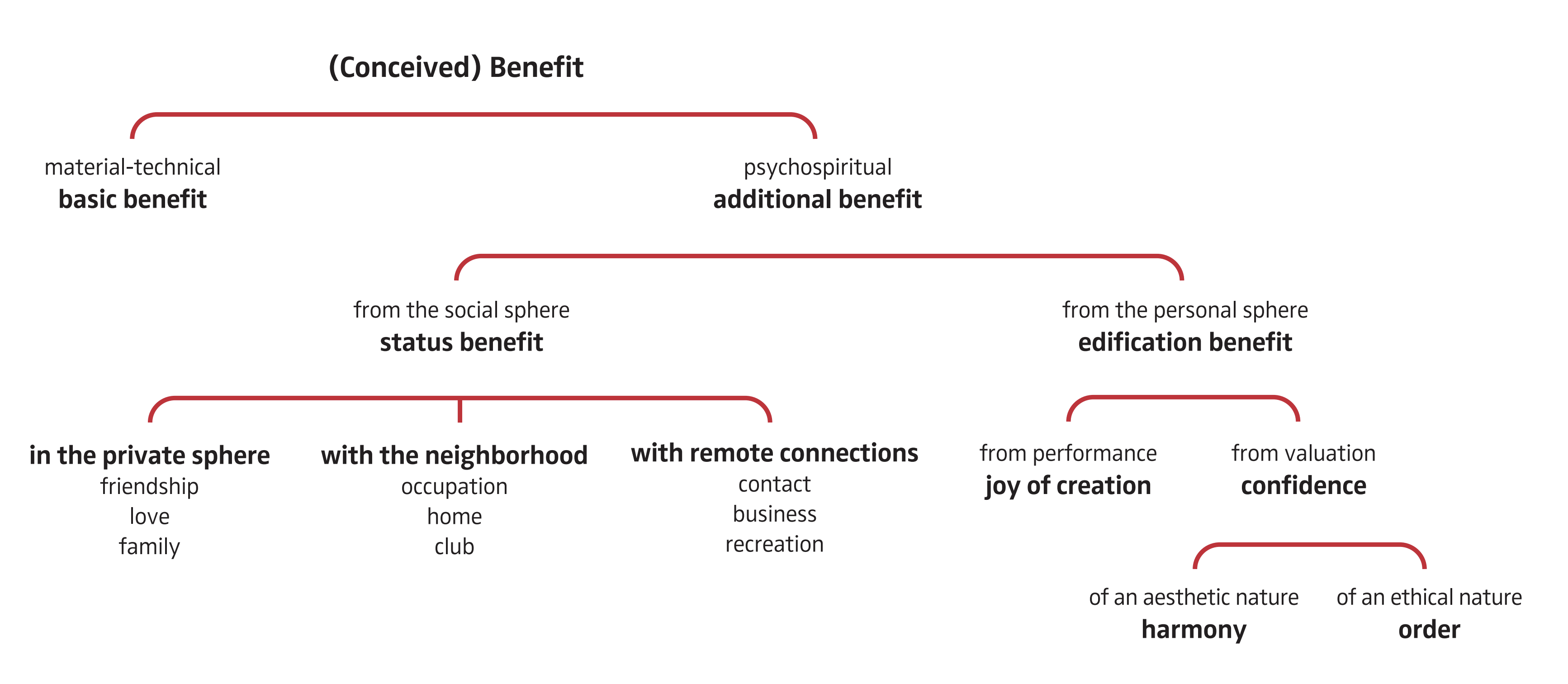

(Conceived) Benefit - the Benefit Scheme of the Nuremberg School

One of Vershofen’s central models for explaining consumer behavior aims to better understand individual perceived utility. Vershofen was familiar with the discussions in economics about market behavior of consumers. He was deeply engaged with topics like the concept of value coined by Adam Smith, the macroeconomic discussions on the role of price, and the concept of utility discussed by Schmalenbach. None of these convinced him completely, especially because none distinguished the highly individual and subjective goals and desires that drive consumers to make purchases.

He contrasted these concepts with his own utility theory built around benefits, which is based on two of his essential propositions:

- Vershofen pointed out early on that the decisive factor for the consumer’s purchase decision is not an objectively “inherent” benefit of the product, but the consumer’s idea and expectation of the benefit – the conceived benefit – at the time of the purchase decision.

- Vershofen emphasized that consumers’ conceived benefits are only partly derived from functional-material aspects, but rather to a considerable extent from immaterial benefit components. For the intangible benefit components, Vershofen published a detailed system that is included in some leading textbooks to this very day.

One of the best available overviews of Vershofen's contribution to a theory of consumer behaviour is the 1963 work of the same name by Hans Moser.

After a brief description of the scientific starting point and the methods and terminology used by Vershofen, the work presents the most important research results in the field of consumer behaviour. This includes theses on the consumer in the market and considerations on benefits and how these can be categorised. The text also contains a critical appraisal and thoughts on the rationality and irrationality of consumer behaviour.

The work is available in a new NIM edition with the same text as the original.

Consumer Behavior: Visible and Invisible Aspects

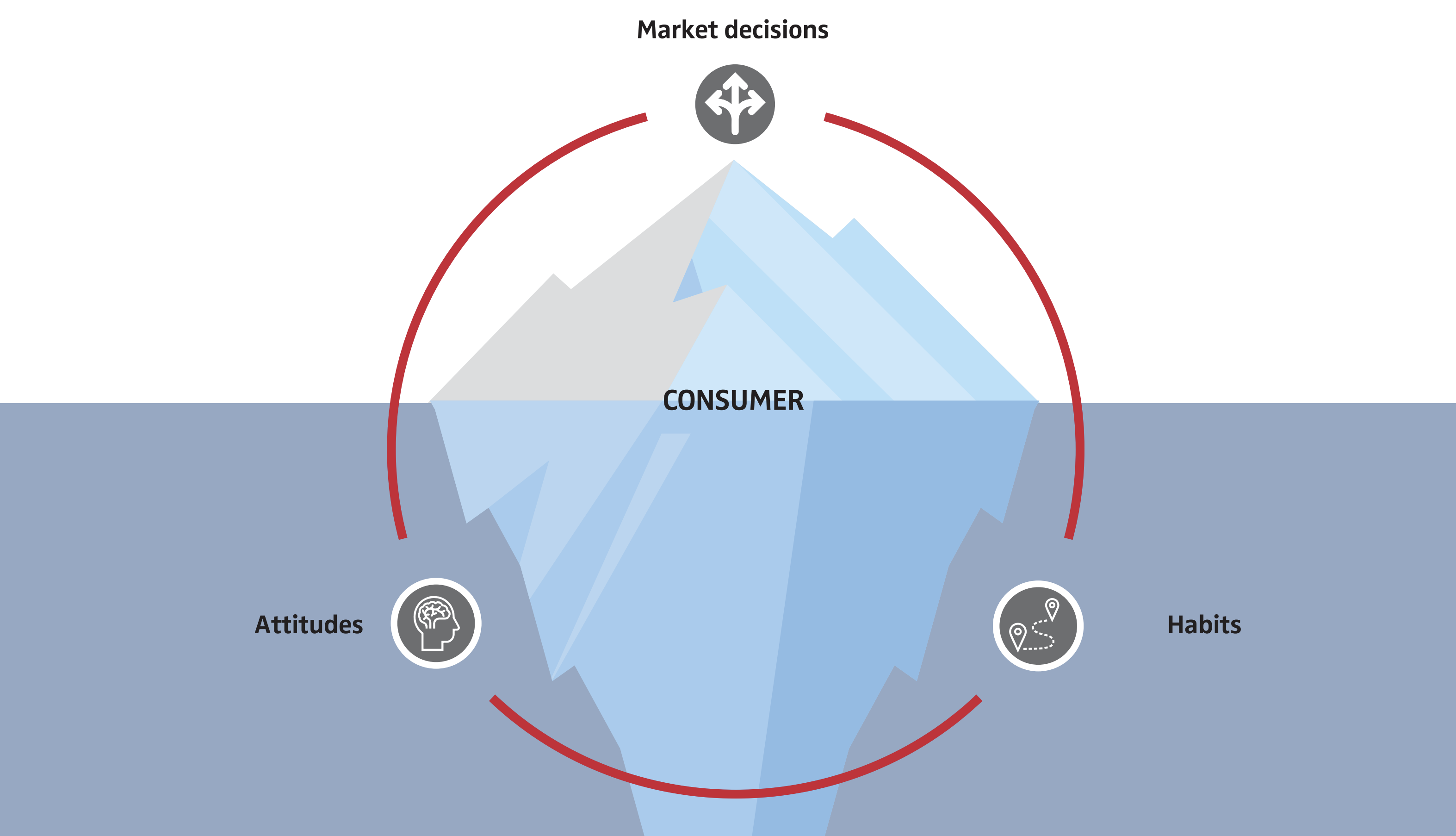

Vershofen’s view of the connection between (visible) market decisions and (invisible) attitudes and habits can be illustrated with an “iceberg metaphor,” even if this was not yet used in Vershofen’s time.

Ultimately, long before the North American literature, Vershofen anticipated the need to move from viewing consumers as a “black box” in stimulus-response models to viewing people from a stimulus-organism-response perspective. The human being as an organism with its component “attitudes and habits” identified by Vershofen represents the missing link between marketing stimuliand market decisions of consumers.